There is a profound behavioural divide in our society’s attitude between ‘disease of the body’ and ‘disease of the mind.’ It is well researched that physical and mental health are fundamentally connected and have significant impact on the quality of life one has, as well as the demands on financial strain on the healthcare system (Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA), 2018). The medical model implies mental illness “is not on par with physical health” (Davey, 2013). Treatment and attitudes in the public and health sectors of mental health is not granted the same empathy as physical illness.

This blog will serve as a systematic review of societal norms that provides insight to the definition of health, social determinants which limit aid, vulnerability factors that affect those with mental health challenges, and a review on influence of stigma in the mental health community. Finally, it will illustrate how change can be the driving factor to improve the lives of individuals with mental illness and improve society’s understanding in the area of mental illness.

Mental illness has a deep impact on a micro and macro scale in human society. Reports from the World Health Organization (WHO) (2018) suggests the following facts of mental illness that cause an impact on a global scale.

In Canada, the Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC) (2018) suggests the following statistics of the impact on mental health:

Wellness

Before exploring the depths of discrimination faced by the vulnerable and marginalized population afflicted by mental illness, one must understand how wellness or health is defined through society’s norms and needs. In 1948, WHO defined health as a, “state of complete physical, mental, and social well being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” In the past 60 years this definition has not changed or adapted to the growing health needs observed in our society. Recognizing this disproportion, researchers have attempted to illustrate the importance of elaborating on this definition to account for our evolving societies. The largest proposed change to the definition is the idea that individuals have the ability and resilience to live with chronic disease due to the new treatments promoting increased life expectancy with new treatment models that empower patients to persist against their affliction (Huber, 2011). Individuals with chronic illness now have the potential support to maintain a balance between psychological, physical, socioeconomic, cultural and spiritual factors that contribute to their overall wellness (Bishop & Yardley, 2010).

Vulnerability

Individuals living with mental illness are deemed a vulnerable segment of our population as they are at an increased risk of physical, emotional, psychological, and socioeconomic harm compared to others who do not share the same affliction (Grazier, Smiley & Bondalapati, 2016). There are many health consequences that affect this population such as:

- Lower life expectancy

- Increased chance of chronic illness

- Work absenteeism

- Homelessness

- Poverty

- Unemployment

(Grazier, Smiley & Bondalapati, 2016)

Social Determinants of Health

WHO (2018) explored reasons why individuals with mental health challenges are placed at a higher degree of vulnerability, which are:

- Social stigma and discrimination

- Exposure to high rates of physical and sexual violations

- Restriction of their political/civil rights

- Reduced access to essential health and emergency support services

- Social/economic barriers to education and employment

- Increased risk of homelessness and poverty

- Limited support programs or excluded from existing resources

Individuals with mental illness also have a greater risk of experiencing injustice in terms of health inequalities and limited access to resources to meet their basic needs. Instituting health equity to the forefront of the Canadian medical system will improve the overall wellness of society by allocating proper resources to those in need.

Health inequalities exist which impacts one’s, “health status of individuals and groups due to one’s genes or individual choices” (Government of Canada, 2018). On the other hand, health inequity is, “one or more health inequalities that are unfair or unjust and are modifiable” (Government of Canada, 2018) The Government of Canada, (2018) has recognized a list of determinants of health, which include:

- Income and social status

- Employment and working conditions

- Education and literacy

- Childhood experiences

- Physical environment

- Social supports and coping skills

- Healthy behaviours

- Access to health services

- Biology and genetic endowment

- Gender

- Culture

Individuals with mental illness are faced with greater exposure and vulnerability to adverse social, economic, and environmental circumstances that are aligned with social determinants; which have a lifestyle influence on one’s health (impacting all ages) and have profound impacts on one’s development (WHO, 2014). Research by WHO (2014) suggests:

- Depression is linked with low socioeconomic positions.

- Women experience an increase of unjust social, economic, and environmental factors compared to men.

- Mental illness has a correlation with low income, lack of education, marital disadvantage, and unemployment.

- Young people are at a 2.5 times risk of developing social inequalities with a lower socioeconomic status then those young people with a higher socioeconomic status.

- Children with mothers afflicted with mental illness are at a 5 times greater risk of developing mental illness.

- Adolescents in poverty with poor education and distant connection with family, peers and community have an increased risk of developing emotional challenges, engaging in risk behaviours (i.e. substance use), and not making informed decisions.

Social-Ecological Model

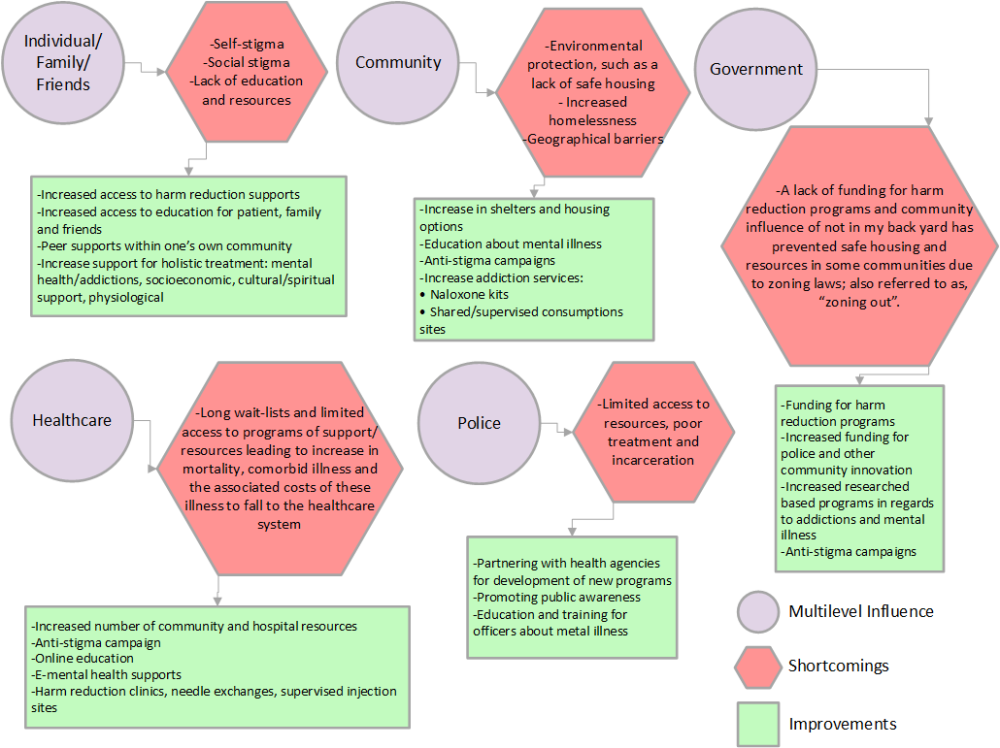

When looking at the inequalities individuals with mental illness face, it is key to use a multi-level system approach (specifically the social-ecological model (SEM)) which explores the impacts of the inequalities and barriers by analyzing the relationship between the individual, community, healthcare system, law enforcement, and the government (Galea, 2015). Please see the diagram below to highlight some of these injustices individuals with mental illness are faced with, as well as some positive strides to improve the quality of life for individuals with mental illness:

(Bardwell et al., 2017; Connell, Gilreath, Aklin & Brex, 2010; Merz, 2014; Vancouver Police Department 2017; Vancouver Coastal Health, 2017; The Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions, 2017)

Understanding these barriers to mental health has required the need of a global approach to develop a platform to improve social norms, values, practices, and empowerment through the use of, “social inclusion, community freedom from discrimination and violence and access to economic resources” (WHO, 2014, p.43). This will help improve the well-being of individuals with mental illness and prevent social inequalities (WHO, 2014). To advance this approach, research suggests that social determinants of health should be screened by all professionals that collaborate in the patient’s care, which will allow for the optimization of one’s health needs and provide access to resources (WHO, 2014). It is key to note that one’s wellness is influenced by the, “interaction between one’s potential, demands of life, and environmental determinants” (WHO, 2014).

Stigma

Individuals with mental illness are faced with the challenges of their disorder as well as society’s overpowering stigma towards mental illness. 1 in 5 Canadians are exposed to mental illness every year, which means 7 million Canadians are influenced by societal stigma leading to worsening health outcomes (MHCC, 2018). Even with this knowledge and prevalence of mental illness, stigma remains strong within our communities and impacts the health of individuals with mental illness. Stigma is still a global problem, evident in hospitals, schools, workplaces, within friends & families, the media, and communities (MHCC, 2018).

Stigma against mental illness impacts one’s overall wellness, as prejudices and stereotypes create negative beliefs about these individuals (Corrigan & Watson, 2002). A common misconception of individuals with mental illness is they are possibly “dangerous and incompetent” (Corrigan & Watson, 2002), which leads to avoidance and withholding of services because of the discriminatory behavioural component of stigma (Corrigan & Watson, 2002).

Individuals with mental illness also inflict self-stigma, such as negative self beliefs and emotional reactions (weak, shame, hopeless, low self-esteem), which can then lead to behavioural responses (avoidance, not seeking help) (Corrigan & Watson, 2002).

(Psychological Sciences Institute, 2016)

(The Royal Mental Health Centre, 2018)

Due to this, individuals with mental illness are robbed of wellness, jobs, safe housing, healthcare, and socioeconomic supports. Research suggests that 60% of individuals with mental health challenges do not pursue help due to the profound stigma in society (MHCC, 2018). Symptomology is worsened as a result of not seeking treatment, impairing all areas of one’s life and have feelings of devalue and dehumanization (MHCC, 2018). The MHCC has many innovations to actively decrease the influence of stigma. The MHCC (2018) suggests that behavioural and attitude change is required by our society to encourage respect, acceptance, and equality to people with mental illness. This change in conduct will lead to better quality of life for individuals with mental illness and decrease burden on the healthcare system (MHCC, 2018). The acknowledgement that mental illness ‘is not a choice’ and with proper treatment and support, recovery can be hopeful (MHCC, 2018). The MHCC (2018) has promoted anti-stigma campaigns across Canada targeting healthcare professionals, youth, working people, and the media.

E-Mental Health

Challenges such as limited resources, wait-lists, geographical barriers, and stigma are currently being combated with the innovation of Canada’s e-mental health. This new approach is transforming the way care can be delivered, by providing and empowering patients through the use of smart phones, social media campaigns, and games (Hatcher, Mahajan, Schellenberg & Thapliyal, 2014). To meet the demands of Canadian residents, a push for online medical support can and has benefited many members of society. E-mental health is defined as, “mental health services and information delivered or enhanced through the internet and related technologies” (Hatcher et al., 2014, p.4). The use of e-mental health provides additional benefits to the traditional healthcare system and individuals are empowered through collaboration with healthcare professionals and supplemental knowledge. This enables the patient to control (in a healthy manor, i.e. still subject to healthcare recommendations and standards) their treatment delivery, as the health care provider is no longer the, ‘vessel of all the knowledge’ (Hatcher et al., 2014). With the general universal increase in technological ability, these online supports can now reach the majority of all age groups and genders in Canada’s diverse society. Access, anonymity, autonomy, preventing stigma, and encouraging all age groups to seek support has led to a positive shift in how individuals seek support and monitor their symptoms (Hatcher et al., 2014; Polgar, 2018). Although this is new territory for Canada’s mental health services, future growth will allow for increased services that will offer individuals a better understanding for their illness. It is key that Canada’s mental health system continue to adapt to the ever-changing healthcare system needs through the use of technology to prevent a gap in service to an already underserviced segment of the population.

The field of mental health is a diverse, under represented, and under supported area in the healthcare system and society. There have been steady incremental improvements annually. However, society has yet to meet the basic needs of life for individuals with mental illness. The profound discrimination and social injustices individuals are faced with is alarming and reinforces the vulnerability of these individuals. To improve these individual’s quality of life, society will need to overcome the social determinants of health that are impeding their lives and change the culture around stigma and the past social norms of mental illness. This can be conducted through the use a multilevel health approach to strengthen relationships in our society and to provide better care and support those afflicted with metal illness. Mental health needs to be given the same importance as physical health and not treated as a separate issue. No matter the disease or disorder, all members of Canada deserve fair access to treatment and recovery models to promote one’s wellness to their fullest.

References

Bardwell, G., Collins, A.B., McNeil, R., &Boyd, J. (2017). Housing and overdose: an opportunity for the scale-up of overdose prevention interventions? Harm Reduction Journal 14(77), 1-4. doi:10.1186/s12954-0170203-9

Bishop,F., & Yardley, L. (2010). The development and initial validation of a new measure of lay definitions of health: The wellness beliefs scale. Psychology and health 25(3): 271-287. doi: 10.1080/08870440802609980

Butler, E. (2015). Mental illness and disorders are not adjectives. Panther Print. Retrieved from: https://hjhspantherprint.com/2455/opinion/mental-illness-and-disorders-are-not-adjectives/

Canadian Mental Health Association. (2018). Connection between mental and physical health. Retrieved from: https://ontario.cmha.ca/documents/connection-between-mental-and-physical-health/

Collard, C.S., Lewinson, T., & Watkins, K. (2014). Supportive housing: an evidence-based intervention for reducing relapse among low income adults in addiction recovery. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work 11(5), 468-79. doi: 10.1080/15433714.2013.765813

Connell, C.M., Gilreath, TA.D., Aklin, W.M., & Brex, R.A. (2010). Social-ecological influences on patterns of substance use among non-metropolitan high school students. American Journal of Community Psychology 45 (1-2), 26-48. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9289-x

Corrigan, P.W., & Watson, A.C. (2002). Understanding the impact of stigma on people with mental illness. World Psychiatry 1(1). 16-20. Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1489832/

Creighton, J. (2014). If physical diseases were treated like mental illness. Futurism. Retrieved from:

https://futurism.com/physical-diseases-treated-like-mental-illness/

Davey, G. C. L. (2013). Mental health & stigma. Psychology Today. Retrieved from: https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/why-we-worry/201308/mental-health-stigma

Galea, S. (2015). The determination of health across the life course and across levels of influence. School of Public Health. Retrieved June 15, 2018 from: https://www.bu.edu/sph/2015/05/31/the-determination-of-health-across-the-life-course-and-across-levels-of-influence-2/

Government of Canada. (2018). Social Determinants of Health. Retrieved June 6, 2018 from: http://cbpp-pcpe.phac-aspc.gc.ca/public-health-topics/social-determinants-of-health/

Grazier, K.L., Smiley, M.L., & Bondalapati, K.S. (2016). Overcoming barriers to integrating behavioural health and primary services. Journal of Primary Care and Community Health 7(4), 242-248. doi: 10.1177/2150131916656455

Hatcher, S., Mahajan, S., Schellenberg, M., & Thapliyal, A. (2014). E-Mental Health in Canada: Transforming the mental health system using technology. Retrieved from: https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/sites/default/files/MHCC_E-Mental_Health-Briefing_Document_ENG_0.pdf

Huber, M. (2011). Health: How should we define it? British Medical Journal 343(7817), 235 237.

Mental Health Commission of Canada. (2018). Stigma and Discrimination. Retrieved from: https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/English/what-we-do/stigma-and-discrimination

Merz, T. (2014). Why do men take more drugs than women? The Telegraph. Retrieved from: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/men/thinking-man/11000117/Why-do-men-take-more-drugs-than-women.html

Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions (2017). Responding to BC’s overdose epidemic. Retrieved from: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/health/about-bc-s-health-care-system/office-of-the-provincial-health-officer/overdose_response_progress_update_nov_december2017.pdf

Psychological Sciences Institute. (2016). Don’t equate the individual with the illness. Retrieved from:

https://www.psisl.org/2016/11/22/what-can-you-do-about-mental-health-stigma/

Polgar, D.R. (2018). What is the future of mental health technology. Retrieved from: https://www.ibm.com/blogs/insights-on-business/ibmix/future-mental-health-technology/

Shaffer, B. (2015). Breaking the prejudice of mental illness. Odyssey. Retrieved from: https://www.theodysseyonline.com/breaking-the-stigma-of-mental-illness

The Royal Mental Health Centre. (2018). Definition self stigma. Retrieved from https://www.slideshare.net/theroyalott/selfstigma

Vancouver Costal Health (2017). Harm Reduction. Retrieved from: http://www.vch.ca/public-health/harm-reduction

Vancouver Police Department (2017). The opioid crisis: the need for treatment on demand review and recommendations. Retrieved from: https://vancouver.ca/police/assets/pdf/reports-policies/opioid-crisis.pdf

World Health Organization. (2014). Social determinants of mental health. Retrieved from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/112828/9789241506809_eng.pdf;jsessionid=0DB41A4A1E9D6C49D2B340584C3818DD?sequence=1