A Look at Simulation in Healthcare

Education in health disciplines is dynamic and requires creative and effective ways to provide learners with enriched learning opportunities, while incorporating changes influenced by research, technology and system demands. The pedagogical tool of simulation has become a popular strategy to meet the growing needs of learners, patients’ well-beings and the healthcare system. The purpose of this entry is to analyze current literature and discuss the background, theoretical framework, advantages and disadvantages of simulation-based education (SBE). In nursing education, specifically in hospital setting, SBE teaching strategies can be applied to advance a nurse’s skill set while improving patient safety and care. By exploring the current literature, it provides educators an opportunity to identify useful pedagogical tools for future teaching opportunities.

Use of Simulation in Healthcare

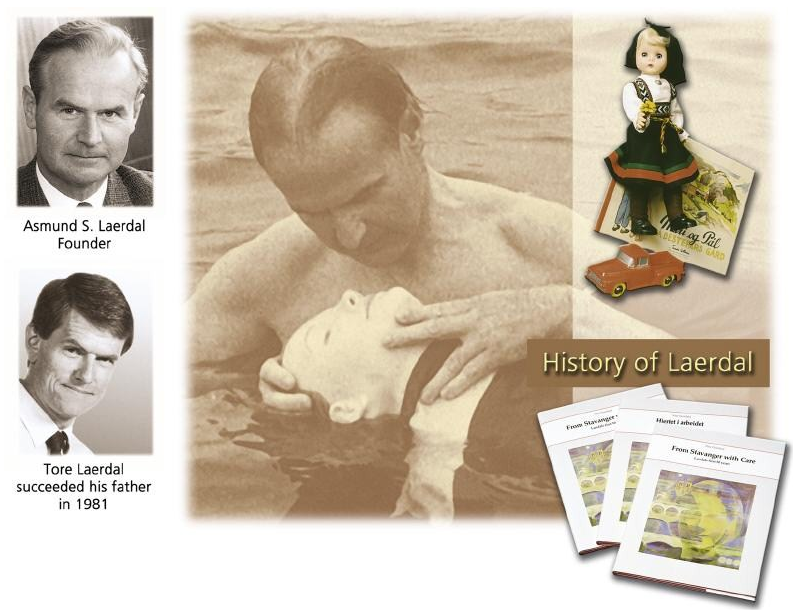

The use of simulation in healthcare was developed by Peter Safar and Asmund Laerdal in 1950 with the invention of the Rescue CPR Annie (Laerdal, 2020), as observed in the figure below. Al-Elq (2010) states that simulation, “refers to an artificial representation of a real-world process to achieve educational goals and experiences… [healthcare, simulation is] any educational activity that utilizes simulation aide to replicate clinical scenarios” (p.35). Healthcare SBE bridges knowledge obtained in a classroom with a real-life clinical experience through goal-based skill practice without risk to real patients (Al-Elq, 2010).

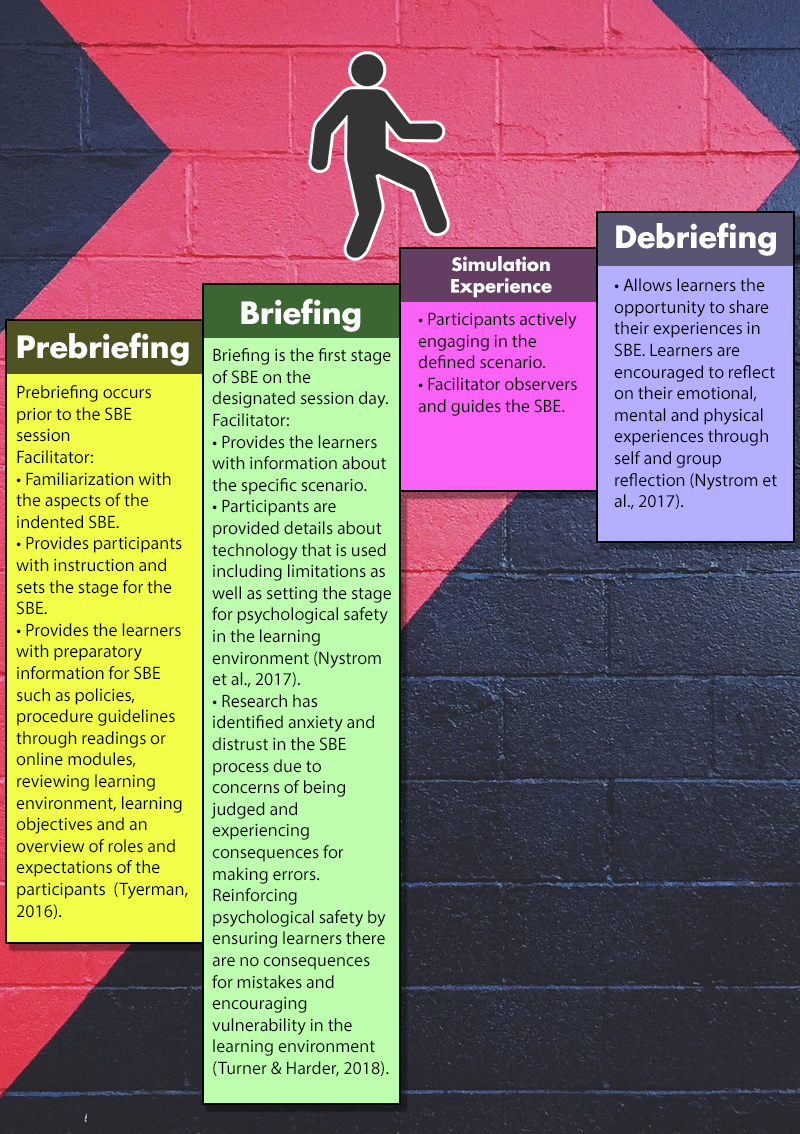

Similar to other pedagogical strategies, there are a number of different approaches to SBE that can be used by trained facilitators. SBE approaches consist of the same four foundational phases seen in the framework below:

Theoretical Framework

SBE is related to the progressive philosophy of adult education, which focuses on the experiential and problem-solving method of learning (Melrose et al., 2015). In SBE, a learner has the opportunity to be exposed to real-life situations while having the opportunity to apply critical thinking and practical knowledge to solve the task at hand (Melrose et al., 2015). SBE also correlates with the behavioural philosophy of education as it focuses on skill development to gain competency. Competency is obtained by practicing new and modifying previously learned skills (Melrose et al., 2015; McGaghie & Harris, 2018). As a facilitator, the use of observation, coaching and constructive feedback are all techniques that support learners in skill development stemming from behavioural philosophy (McGaghie & Harris, 2018).

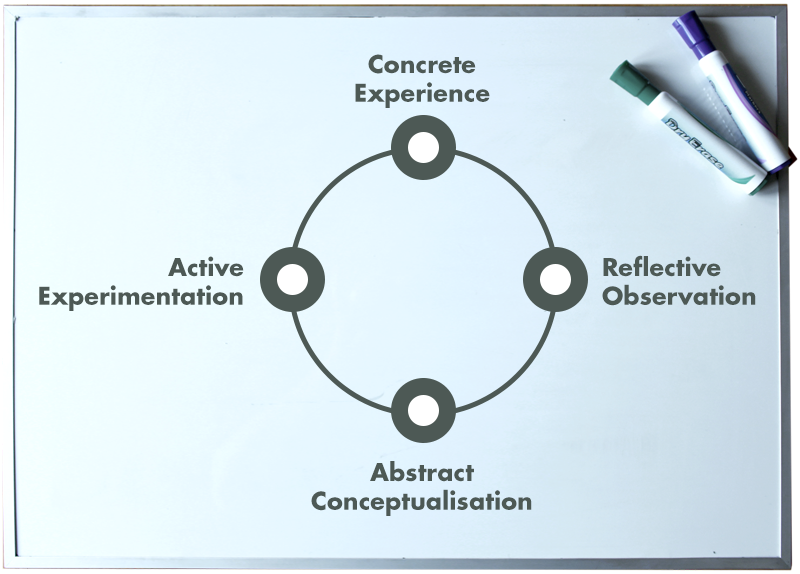

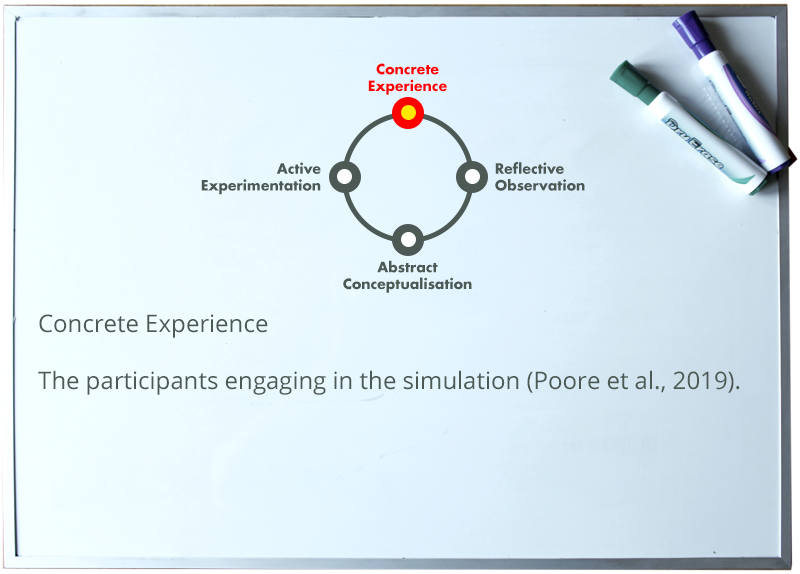

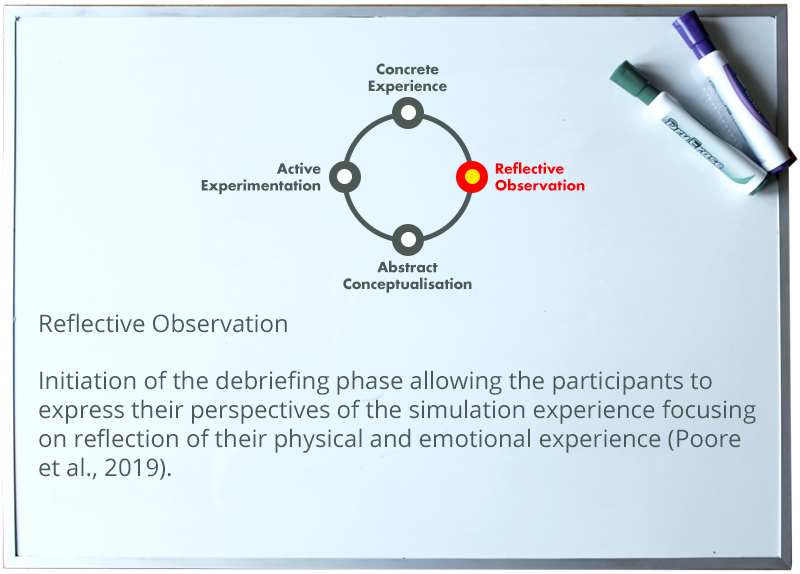

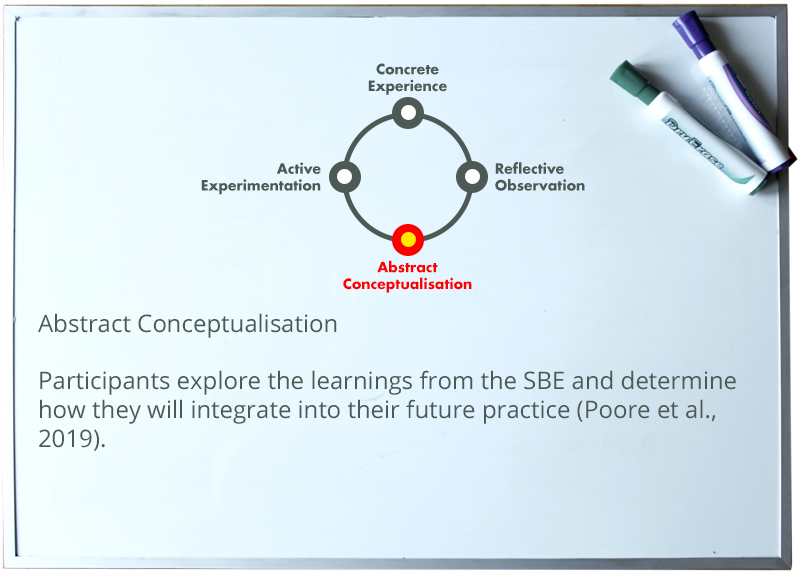

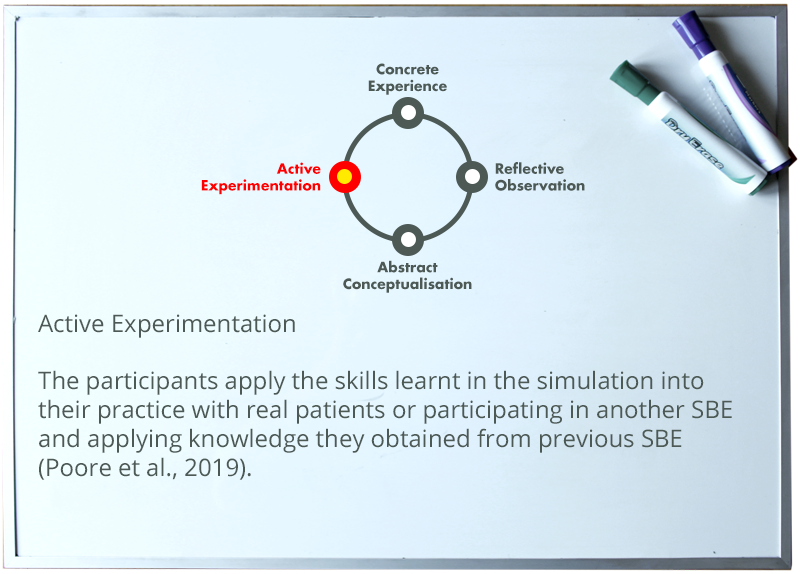

The application of Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory has a profound influence on SBE. Kolb’s theory is based on the assumption that, “learning is the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience” (Kolb, 1984, p.38). This four-stage model allows learners to be exposed to different modes of learning (McLeod, 2017). The following presentation represent the Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory with the application to SBE.

Advantages of SBE

One of the overarching benefits of SBE is the positive impact it has on patient care. As patient acuity and complexity continue to rise, nurses are required to have advanced skill sets to maintain safe care (Harder, 2010; Lateef, 2010). The use of SBE promotes professional development. Nursing requires the ability to conduct accurate assessment, care planning, implementation of care (procedures or data collection) and observing clinical outcomes. Canadian research indicates that about one-fifth of all nurses in 2015 reported medication errors (Government of Canada, 2016). This occurs due to poor assessment and verification before administration. SBE can be used to allow nurses the opportunity to clinically assess, and engage in safe medication administration (Durham & Alden, 2008). By participating in SBE, learners gain transferable skills that can be implemented to clinical practice to limit risk to real patients such as medication administration.

SBE can also benefit nurses with the opportunity to engage in rarely used practices that require accuracy and knowledge (Lateef, 2010; Harder, 2010). For example, the use of mock code blue drills ensures safe response in a timely manner. Additionally, with the implementation of new practices, SBE allow nurses the opportunity to practice and have educational support to ensure correct technique is completed before attempting the new skill on a real patient (Lateef, 2010; Harder, 2010).

Finally, to provide holistic patient care, nurses are part of an interdisciplinary team. SBE can aid in developing effective teamwork. A team that has jeopardized communication places patients and team members at risk. Some risks include limited communication around clinical decisions, the inability to communicate priorities of care and limiting the sharing of valuable assessment and care planning date (Marshall & Flanagan, 2010). SBE allows for interdisciplinary team training in a safe place to practice, give and receive constructive feedback on technical and non-technical skills, and engage in a debrief (Nystrom et al., 2017). These sessions allow for each member to obtain role clarity and division of skills when providing team collaboration of care to ensure fluid interactions. This is extremely important when providing crisis response (Nystrom et al., 2017).

Disadvantages of SBE

The literature has identified a number of challenges associated with SBE including cost and availability. The initial investment for an organization, as well as, the ongoing maintenance of equipment can be steep. Costs are dependent on the specific modality used in training session including programmed manikins, computerized on-screen simulation, actors and staff to facilitate and provide background support to the SBE (Krihnan et al., 2017). Another cost is backfilling nurses attending training sessions and require replace for their regular patient care duties. Nurses are faced with increased workload demands and have limited time for education sessions (Krihnan et al., 2017). To help overcome these barriers, an educator must determine what modality is required for the defined learning objectives which will help determine financial and time investment.

Another challenge with SBE is ensuring trained facilitators are available. To ensure the effectiveness of the SBE and psychological safety, facilitators are required to develop curriculum that is evidence-based and transferable to practice (Roh et al., 2016). They also must be able to engage participants, mentor and supports learners and adjust the scenario on the fly to ensure learning objectives are met (Boese et al., 2013). A low number of trained facilitators in SBE, within organizations can cause burnout. To increase the number of educators with SBE competencies, the use of workshops and online learning (Roh et al., 2016) can be used.

Strategies to Teaching

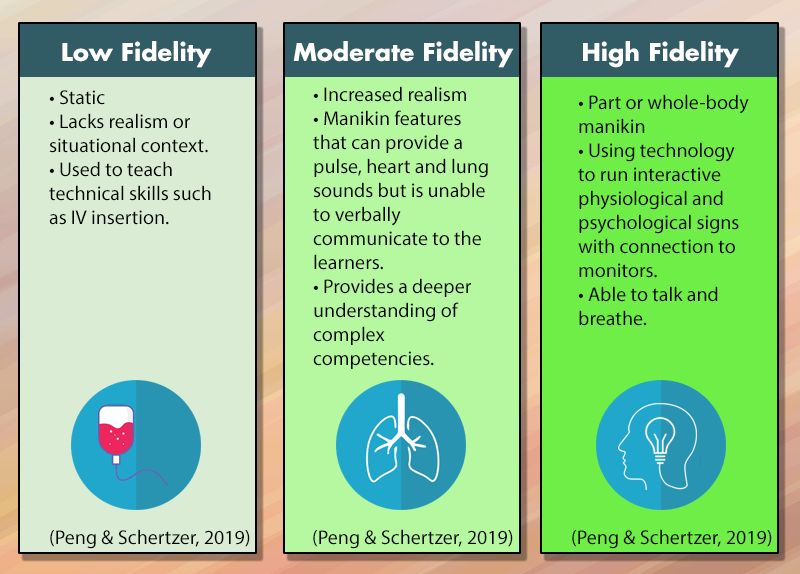

Prior to determining the methodology and learning outcomes of their sessions, educators must consider the purpose of an SBE. This can include developing skills, practicing procedures, improving team communication, gaining experience with crisis management through mock drills and developing improvements in systems, by identifying inefficiencies in existing systems (Peng & Schertzer, 2019). After an educator has determined the purpose of the simulation, a methodology can be applied that suites the learning objectives (Peng & Schertzer, 2019). This includes determining the classification of SBE, which is divided into three categories:

SBE approaches vary dependent on the debriefing phase. Traditional simulation uses debrief at the end of the active simulation. Another approach is rapid cycle deliberate which focuses on skill repetitiveness and debriefing through out the simulation. This approach allows for continuous improvement through out SBE (Peng & Schertzer, 2019).

Conclusion

SBE is a multi-model approach that has shown benefits, not only for learners in nursing, but also for patients and the healthcare system. It provides nurses the opportunity to refresh and advance vital skills to maintain their practice in the ever-evolving workplace and meet the needs of their patients. SBE permits nurses the opportunity to be exposed to real life situations without jeopardizing patient safety, while having the opportunity to apply these skills to real clinical experiences. SBE also enhances team communication and collaboration in healthcare settings to ensure quality care is provided. While budget and investment in time continue to be a barrier to implementation; ongoing research, advances in technology and innovative teaching strategies are providing accessibility to SBE for educators to meet the training demands while eliminating the barriers currently impeding the implementation of this pedagogy.

References

Al-ELq. A. H. (2010). Simulation-based medical teaching and learning. Journal of Family and Community Medicine, 17(1), 35-40. doi: 10.4103/1319-1683.68787

Boese, T., Cato, M., Gonzalez, L., Jones, A., Kennedy, K., Reese, C., Decker., S., Franklin, A.E., Gloe, D.,G., Lioce, L., Meakim, C., Sando, C.R., & Borum, J.C. (2013). Standard of best practice: Simulation Standard V: Facilitator. Clinical Simulation In Nursing, 9(6), S22-S25. doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2013.04.010

Durham, C.F., & Alden, K.R. (2008). Enhancing patient safety in nursing education through patient simulation. Hughes RG, ed. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US).

Government of Canada. (2015). Correlates of medication error in hospitals. Retrieved from Statistics: Canada: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-003-x/2008002/article/10565/5202501-eng.htm

Harder, N. (2010). Use of simulation in teaching and learning in health sciences: A systematic review. Journal of Nursing Education, 49(1), 23-28. doi:10.3928/01484834-20090828-08

Laerdal. (2020). Laerdal History. Retrieved from https://www.laerdal.com/us/docid/1117121/Laerdal-History

Kolb, D., A., Rubin, I.M., & McIntyre, J.M. (1984). Organizational psychology: Reading on Human behavior in organizations. Englewood, Cliffs, NJ: Prentice- Hall.

Krihnan, D.G., Vasu Keloth, A, & Ubedulla, S. (2017). Pro and cons of simulation in medical education: A review. International Journal of Medical and Health Research, 3(6), 84-87.

Lateef, F. (2010). Simulation-based learning: Just like the real thing. Journal of Emergencies, Trauma, and Shock, 3(4), 348-352. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.70743

Marshall, S., Flanagan., (2010). Simulation-based education for building clinical teams. Journal of Emergencies, Trauma and Shock, 3(4), 360-368). doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.70750

McGaghie, W.C., Harris, I.B. (2018). Learning theory foundations of simulation-based mastery learning. Society for Simulation in Healthcare, 13(3S), 15-20.

McLeod, S. (2017). Kolb’s learning styles and experiential learning cycle. Retrieved from https://www.simplypsychology.org/learning-kolb.html

Melrose, S., Park, C. & Perry, B. (2015). Instructional immediacy: The heart of collaborating and learning in groups. In Teaching health professionals online: Frameworks and strategies. Athabasca, AB, Canada: AU Press.

Nyström, S., Dalberg, J., Edelbring, S., Hult, H., Dahlgren, M.A. (2017). Continuing professional development: pedagogical practices of interprofessional simulation in health care. Studies in Continuing Education, 30(3), 303-319. doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2017.1333981

Peng, C.R., & Schertzer, K. (2019). Rapid cycle deliberate practice in medical simulation. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551533/

Poore, J.A., Cullen, D.L., Schaar, G. L. (2014). Simulation-based interprofessional education guided by Kolb’s experimental learning theory. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 10(5), e241-e247. doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2014.01.004

Roh, Y. S., Kim, M. K., & Tangkawanich, T. (2016). Survey of outcomes in a faculty development program on simulation pedagogy. Nursing and Health Sciences 18(2), 210–215. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12254

Turner, S., Harder, N. (2018). Psychological safe environment: a concept analysis. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 18, 47-55. doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2018.02.004

Tyerman, J., Luctkar-Flude, M., Graham, L., Coffey, S., Olsen-Lynch, E. (2016). Pre-simulation preparation and briefing practices for healthcare professionals and students: A systemic review protocol. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports. 80-89.